Table of Contents

- 1. String format() Parameters

- 2. Return value from String format()

- 3. How String format() works?

- 4. Basic formatting with format()

- 5. Numbers formatting with format()

- 6. String formatting with format()

- 7. Formatting class and dictionary members using format()

- 8. Arguments as format codes using format()

- 9. Extra formatting options with format()

The string format() method formats the given string into a nicer output in Python.

The syntax of the format() method is:

template.format(p0, p1, ..., k0=v0, k1=v1, ...)

Here, p0, p1,… are positional arguments and, k0, k1,… are keyword arguments with values v0, v1,… respectively.

And, template is a mixture of format codes with placeholders for the arguments.

1. String format() Parameters

format() method takes any number of parameters. But, is divided into two types of parameters:

- Positional parameters – list of parameters that can be accessed with index of parameter inside curly braces

{index} - Keyword parameters – list of parameters of type key=value, that can be accessed with key of parameter inside curly braces

{key}

2. Return value from String format()

The format() method returns the formatted string.

3. How String format() works?

The format() reads the type of arguments passed to it and formats it according to the format codes defined in the string.

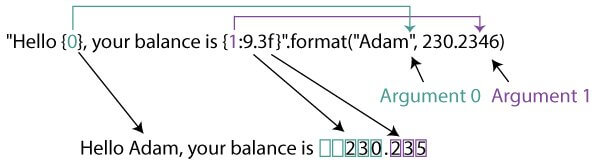

3.1. For positional arguments

Here, Argument 0 is a string “Adam” and Argument 1 is a floating number 230.2346.

Note: Argument list starts from 0 in Python.

The string "Hello {0}, your balance is {1:9.3f}" is the template string. This contains the format codes for formatting.

The curly braces are just placeholders for the arguments to be placed. In the above example, {0} is placeholder for “Adam” and {1:9.3f} is placeholder for 230.2346.

Since the template string references format() arguments as {0} and {1}, the arguments are positional arguments. They both can also be referenced without the numbers as {} and Python internally converts them to numbers.

Internally,

- Since “Adam” is the 0th argument, it is placed in place of

{0}. Since,{0}doesn’t contain any other format codes, it doesn’t perform any other operations. - However, it is not the case for 1st argument 230.2346. Here,

{1:9.3f}places 230.2346 in its place and performs the operation 9.3f. - f specifies the format is dealing with a float number. If not correctly specified, it will give out an error.

- The part before the “.” (9) specifies the minimum width/padding the number (230.2346) can take. In this case, 230.2346 is allotted a minimum of 9 places including the “.”.

If no alignment option is specified, it is aligned to the right of the remaining spaces. (For strings, it is aligned to the left.) - The part after the “.” (3) truncates the decimal part (2346) upto the given number. In this case, 2346 is truncated after 3 places.

Remaining numbers (46) is rounded off outputting 235.

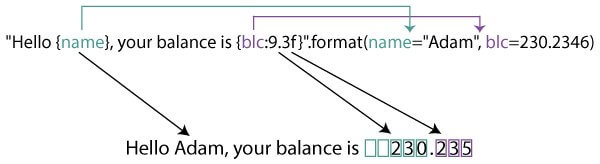

3.2. For keyword arguments

We’ve used the same example from above to show the difference between keyword and positional arguments.

Here, instead of just the parameters, we’ve used a key-value for the parameters. Namely, name=”Adam” and blc=230.2346.

Since these parameters are referenced by their keys as {name} and {blc:9.3f}, they are known as keyword or named arguments.

Internally,

- The placeholder {name} is replaced by the value of name – “Adam”. Since it doesn’t contain any other format codes, “Adam” is placed.

- For the argument blc=230.2346, the placeholder {blc:9.3f} is replaced by the value 230.2346. But before replacing it, like previous example, it performs 9.3f operation on it.

This outputs 230.235. The decimal part is truncated after 3 places and remaining digits are rounded off. Likewise, the total width is assigned 9 leaving two spaces to the left.

4. Basic formatting with format()

The format() method allows the use of simple placeholders for formatting.

4.1. Example 1: Basic formatting for default, positional and keyword arguments

# default arguments

print("Hello {}, your balance is {}.".format("Adam", 230.2346))

# positional arguments

print("Hello {0}, your balance is {1}.".format("Adam", 230.2346))

# keyword arguments

print("Hello {name}, your balance is {blc}.".format(name="Adam", blc=230.2346))

# mixed arguments

print("Hello {0}, your balance is {blc}.".format("Adam", blc=230.2346))

Output

Hello Adam, your balance is 230.2346. Hello Adam, your balance is 230.2346. Hello Adam, your balance is 230.2346. Hello Adam, your balance is 230.2346.

Note: In case of mixed arguments, keyword arguments has to always follow positional arguments.

5. Numbers formatting with format()

You can format numbers using the format specifier given below:

| Type | Meaning |

|---|---|

| d | Decimal integer |

| c | Corresponding Unicode character |

| b | Binary format |

| o | Octal format |

| x | Hexadecimal format (lower case) |

| X | Hexadecimal format (upper case) |

| n | Same as ‘d’. Except it uses current locale setting for number separator |

| e | Exponential notation. (lowercase e) |

| E | Exponential notation (uppercase E) |

| f | Displays fixed point number (Default: 6) |

| F | Same as ‘f’. Except displays ‘inf’ as ‘INF’ and ‘nan’ as ‘NAN’ |

| g | General format. Rounds number to p significant digits. (Default precision: 6) |

| G | Same as ‘g’. Except switches to ‘E’ if the number is large. |

| % | Percentage. Multiples by 100 and puts % at the end. |

5.1. Example 2: Simple number formatting

# integer arguments

print("The number is:{:d}".format(123))

# float arguments

print("The float number is:{:f}".format(123.4567898))

# octal, binary and hexadecimal format

print("bin: {0:b}, oct: {0:o}, hex: {0:x}".format(12))

Output

The number is: 123 The number is:123.456790 bin: 1100, oct: 14, hex: c

5.2. Example 3: Number formatting with padding for int and floats

# integer numbers with minimum width

print("{:5d}".format(12))

# width doesn't work for numbers longer than padding

print("{:2d}".format(1234))

# padding for float numbers

print("{:8.3f}".format(12.2346))

# integer numbers with minimum width filled with zeros

print("{:05d}".format(12))

# padding for float numbers filled with zeros

print("{:08.3f}".format(12.2346))

Output

12 1234 12.235 00012 0012.235

Here,

- in the first statement,

{:5d}takes an integer argument and assigns a minimum width of 5. Since, no alignment is specified, it is aligned to the right. - In the second statement, you can see the width (2) is less than the number (1234), so it doesn’t take any space to the left but also doesn’t truncate the number.

- Unlike integers, floats has both integer and decimal parts. And, the mininum width defined to the number is for both parts as a whole including “.”.

- In the third statement,

{:8.3f}truncates the decimal part into 3 places rounding off the last 2 digits. And, the number, now 12.235, takes a width of 8 as a whole leaving 2 places to the left. - If you want to fill the remaining places with zero, placing a zero before the format specifier does this. It works both for integers and floats:

{:05d}and{:08.3f}.

5.3. Example 4: Number formatting for signed numbers

# show the + sign

print("{:+f} {:+f}".format(12.23, -12.23))

# show the - sign only

print("{:-f} {:-f}".format(12.23, -12.23))

# show space for + sign

print("{: f} {: f}".format(12.23, -12.23))

Output

+12.230000 -12.230000 12.230000 -12.230000 12.230000 -12.230000

5.4. Number formatting with alignment

The operators <, ^, > and = are used for alignment when assigned a certain width to the numbers.

| Type | Meaning |

|---|---|

| < | Left aligned to the remaining space |

| ^ | Center aligned to the remaining space |

| > | Right aligned to the remaining space |

| = | Forces the signed (+) (-) to the leftmost position |

5.5. Example 5: Number formatting with left, right and center alignment

# integer numbers with right alignment

print("{:5d}".format(12))

# float numbers with center alignment

print("{:^10.3f}".format(12.2346))

# integer left alignment filled with zeros

print("{:<05d}".format(12))

# float numbers with center alignment

print("{:=8.3f}".format(-12.2346))

Output

12 12.235 12000 - 12.235

Note: Left alignment filled with zeros for integer numbers can cause problems as the 3rd example which returns 12000, rather than 12.

6. String formatting with format()

As numbers, string can be formatted in a similar way with format().

6.1. Example 6: String formatting with padding and alignment

# string padding with left alignment

print("{:5}".format("cat"))

# string padding with right alignment

print("{:>5}".format("cat"))

# string padding with center alignment

print("{:^5}".format("cat"))

# string padding with center alignment

# and '*' padding character

print("{:*^5}".format("cat"))

Output

cat cat cat *cat*

6.2. Example 7: Truncating strings with format()

# truncating strings to 3 letters

print("{:.3}".format("caterpillar"))

# truncating strings to 3 letters

# and padding

print("{:5.3}".format("caterpillar"))

# truncating strings to 3 letters,

# padding and center alignment

print("{:^5.3}".format("caterpillar"))

Output

cat cat cat

7. Formatting class and dictionary members using format()

Python internally uses getattr() for class members in the form “.age”. And, it uses __getitem__() lookup for dictionary members in the form “[index]”.

7.1. Example 8: Formatting class members using format()

# define Person class

class Person:

age = 23

name = "Adam"

# format age

print("{p.name}'s age is: {p.age}".format(p=Person()))

Output

Adam's age is: 23

Here, Person object is passed as a keyword argument p.

Inside the template string, Person’s name and age are accessed using .name and .age respectively.

7.2. Example 9: Formatting dictionary members using format()

# define Person dictionary

person = {'age': 23, 'name': 'Adam'}

# format age

print("{p[name]}'s age is: {p[age]}".format(p=person))

Output

Adam's age is: 23

Similar to class, person dictionary is passed as a keyword argument p.

Inside the template string, person’s name and age are accessed using [name] and [age] respectively.

There’s an easier way to format dictionaries in Python using str.format(**mapping).

# define Person dictionary

person = {'age': 23, 'name': 'Adam'}

# format age

print("{name}'s age is: {age}".format(**person))

** is a format parameter (minimum field width).

8. Arguments as format codes using format()

You can also pass format codes like precision, alignment, fill character as positional or keyword arguments dynamically.

8.1. Example 10: Dynamic formatting using format()

# dynamic string format template

string = "{:{fill}{align}{width}}"

# passing format codes as arguments

print(string.format('cat', fill='*', align='^', width=5))

# dynamic float format template

num = "{:{align}{width}.{precision}f}"

# passing format codes as arguments

print(num.format(123.236, align='<', width=8, precision=2))

Output

*cat* 123.24

Here,

- In the first example, ‘cat’ is the positional argument is to be formatted. Likewise,

fill='*',align='^'andwidth=5are keyword arguments. - In the template string, these keyword arguments are not retrieved as normal strings to be printed but as the actual format codes

fill, align and width.

The arguments replaces the corresponding named placeholders and the string ‘cat’ is formatted accordingly. - Likewise, in the second example, 123.236 is the positional argument and, align, width and precision are passed to the template string as format codes.

9. Extra formatting options with format()

format() also supports type-specific formatting options like datetime’s and complex number formatting.

format() internally calls __format__() for datetime, while format() accesses the attributes of the complex number.

You can easily override the __format__() method of any object for custom formatting.

9.1. Example 11: Type-specific formatting with format() and overriding __format__() method

import datetime

# datetime formatting

date = datetime.datetime.now()

print("It's now: {:%Y/%m/%d %H:%M:%S}".format(date))

# complex number formatting

complexNumber = 1+2j

print("Real part: {0.real} and Imaginary part: {0.imag}".format(complexNumber))

# custom __format__() method

class Person:

def __format__(self, format):

if(format == 'age'):

return '23'

return 'None'

print("Adam's age is: {:age}".format(Person()))

Output

It's now: 2016/12/02 04:16:28 Real part: 1.0 and Imaginary part: 2.0 Adam's age is: 23

Here,

- For datetime:

Current datetime is passed as a positional argument to theformat()method.

And, internally using__format__()method,format()accesses the year, month, day, hour, minutes and seconds. - For complex numbers:

1+2j is internally converted to a ComplexNumber object.

Then accessing its attributesrealandimag, the number is formatted. - Overriding __format__():

Like datetime, you can override your own__format__()method for custom formatting which returns age when accessed as{:age}

You can also use object’s __str__() and __repr__() functionality with shorthand notations using format().

Like __format__(), you can easily override object’s __str__() and __repr_() methods.

9.2. Example 12: __str()__ and __repr()__ shorthand !r and !s using format()

# __str__() and __repr__() shorthand !r and !s

print("Quotes: {0!r}, Without Quotes: {0!s}".format("cat"))

# __str__() and __repr__() implementation for class

class Person:

def __str__(self):

return "STR"

def __repr__(self):

return "REPR"

print("repr: {p!r}, str: {p!s}".format(p=Person()))

Output

Quotes: 'cat', Without Quotes: cat repr: REPR, str: STR